A memorial scene for slain American journalist James Foley, killed by ISIS (the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria) on Aug. 19, 2014.

On cue the feigned shock, manly thumping of chests and tribal war dance began anew.

The videotaped beheading of another U.S. journalist, this time Florida’s Steven Sotloff, two weeks after the execution of New Hampshire’s James Foley, predictably sent the White House’s Nobel Peace Prize Laureate onto Washington’s moral perch and Israel’s propagandists into overdrive.

We know the script and its actors well by now.

Protagonists live in the West, or at least resemble Westerners in general skin tone and/or style of dress. They deploy working class soldiers and use expensive weaponry to shear, shred, pulverize, burn, incinerate and decapitate heads, flesh, bone, bridges, roads, electrical grids, mosques, schools, bunkers, homes, hospitals, sons, daughters, fathers, mothers. In other words, to kill en masse all enemy combatants and unfortunate civilians.* The latter is a well-documented result of dropping bombs into heavily populated areas, but it gets dismissed with a common impersonal euphemism: collateral damage. The good guys, Americans and Israelis, know full well that the “War on Terror” kills at least tens of thousands of civilians, injures and maims hundreds of thousands, and displaces families from the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Guinea. But, since the protagonists know what’s best and they have us glued to CNN and Fox News, we view collateral damage as a penny-ante expense.

Not so for the antagonists. In the Middle East the penny ante has become heavy and unforgivable. So the antagonists kill up close and in our faces; close enough to get our attention, so close they hide their despicable faces. Cloaked in black and wearing a robber’s mask, they crave the media attention and villainous role. Since they lack the West’s crazy expensive, imprecise “precision bombs” they can’t generate mass destruction. Instead, they kill in fewer numbers and exploit each for mass effect. Their psychological warfare is less about collateral damage, more about disturbing our sleep.

The protagonists curse them, threaten them, promise to hunt them and eliminate them, yet without the antihero we wouldn’t be fooled by the heroic costume of our protagonists. You see, ISIS (stands for “Islamic State in Iraq and Syria” but its Hebrew pronunciation is, apparently, “Hamas”), similar to Al-Qaeda and Cold War Communists, etc., plays the foil to the West and its heroic allies. These days, Israel.

So, same as last time, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin “Bibi” Netanyahu will declare the villainous ISIS to be no different than Hamas, and then he’ll imply that black-clad killers are par for the course in Gaza and Israeli-occupied West Bank. It wouldn’t surprise me if he used the threat of ISIS to justify Israel’s arrogant theft this week of 990 Palestinian acres near Bethlehem. Evidently, heroes and their allies operate outside international law, accountable to no one.

Meanwhile, the Washington-Wall Street Military Industrial Complex will be doubling down on its Middle East expansion (aka imperialism). On Tuesday, President Obama approved the deployment of 350 more American troops to Iraq. Soon after the video of Sotloff’s murder was deemed authentic, Obama gave a stern message to ISIS, sounding very much like he was guarding Gotham.

“We will not be intimidated,” he declared, then warned Americans to brace for another long (read: costly) fight. These “horrific acts only unite us as a country and stiffen our resolve to take the fight (to) these terrorists. … Those who make the mistake of harming Americans will learn that we will not forget and that our reach is long and that justice will be served.”**

In that way he has begun to sound like his predecessor “protagonist” and war industry pitchman, George W. Bush. Beheadings, after all, are good for business, all the more if they are captured on film. American outrage is a commodity famously leveraged for financial gain.***

Surely, ISIS knew this. Right? It had the script.

Last month, on cue after the beheading of Foley, Israel’s conservative English-language daily, The Jerusalem Post, stretched this headline across five columns of its front page:

“Obama calls Islamic State a ‘cancer’ after graphic beheading.”

In words measured and (self) righteous, Obama presumably spoke for Americans — and common decency — when he said that he and “all of humanity” were appalled by Foley’s murder. Later in the story, Secretary of State John Kerry played the role of a Judeo-Christian politician rushing off to do battle with Old Testament darkness:

“There is evil in this world, and we have all come face-to-face with it once again. Ugly, savage, inexplicable, nihilistic, and valueless evil.”

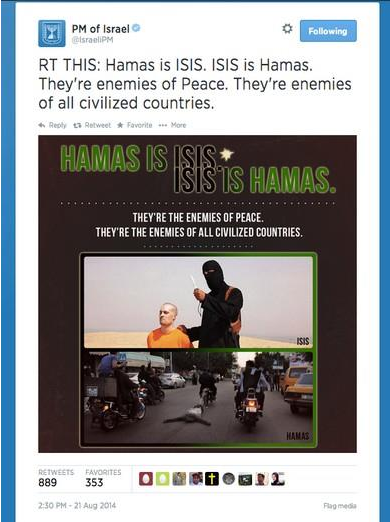

This was the same day the Twitter account of the Israeli Prime Minister posted a still photo of Foley’s execution, as if it justified bombing the bejesus out of Gaza. “RT THIS: Hamas is ISIS. ISIS is Hamas. They’re enemies of Peace. They’re enemies of all civilized countries.”

Followers did as ordered and retweeted Netanyahu’s propaganda 889 times before the post was deleted for its questionable use of Foley’s image.

Screenshot credit: Haaretz newspaper

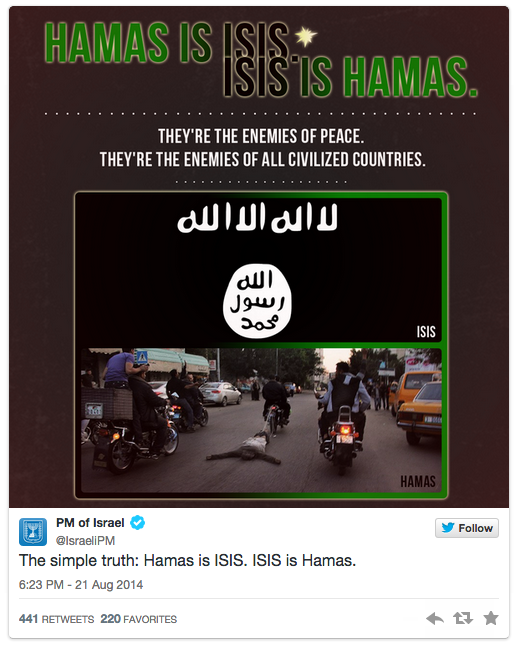

Hours later it resurfaced with Foley’s picture replaced by the Arabic logo for ISIS. This tweet included an additional outrageous claim for any politician — Middle Eastern or Western — to make. It said the truth was simple (never the case in Jerusalem or Washington) and implied that Israel was on the side of it.

“The simple truth: Hamas is ISIS. ISIS is Hamas.”

Screenshot credit: Haaretz newspaper

The following day Israel resumed bombing a dispossessed Muslim people with $110,000 American-made, American-bought Hellfire missiles fired from $20 million American-made, American-bought Apache helicopters. The casualties in Gaza had already exceeded 2,000, the majority of the dead civilian.

A week later, with Israel’s stock of American-made whoop-ass apparently running low and its Iron Dome draining military coffers, Washington routed a boatload of Hellfire missiles to its shore and put a rush on an extra $225 million for its Iron Dome missile defense. Just a little bump to cushion Israel’s annual $3.1 billion American allowance. (Another $126 million bump is due in November.)

Anything, it seems, for Washington’s heroic sidekick.

Or is that backward?

Is Washington the sidekick?

The New Yorker’s Connie Bruck, in an article aptly titled “Friends of Israel,” dissects the influence that Israel lobbyists exact on Washington. In the Sept. 1, 2014 story she describes a tail-wagging-the-dog scene where an influential cadre of senators — Democrats Harry Reid and Tim Kaine; Republicans Mitch McConnell, John McCain and Lindsey Graham — work overtime in late August to ensure Israel is well stocked with U.S. money and missiles. Graham, a hawkish senator from South Carolina and a major recipient of pro-Israel campaign donations, was jubilant after the 11th-hour triumph. Speaking to reporters, he made the extra hundreds of millions of American tax dollars sound like a game of penny ante.

“Not only are we going to give you (Israel) more missiles, we’re going to be a better friend. We’re going to fight for you in the international court of public opinion. We’re going to fight for you in the United Nations.”

—

* If you count just the civilian deaths in Iraq, included in the field reports of U.S. soldiers dated 2004 to 2009, more than half (66,081) of the killed Iraqis were civilian. The dead do not include Iraqis killed during the war’s heaviest fighting in 2003 (when, for example, the U.S. dropped more than 500,000 tons of ordnance on Iraq) or by most coalition forces other than the U.S. military. Iraq Body Count, the British-based nongovernment project that began tracking Iraqi deaths in March 2003, estimates that between 128,431-143,705 civilians in Iraq were killed from the ongoing violence that began with the U.S.-led invasion in March 2003. A database of the deaths is available at Iraq Body Count.

** Lest we count, say, Israel’s attack by air and sea on the USS Liberty, June 8, 1967, killing 34 U.S. crew members and injuring 171. Or, maybe, Rachel Corrie, run over and killed by an armored Israeli Defense Forces bulldozer on March 16, 2003 in the Gaza Strip. She was attempting to block the demolition of a Palestinian home. Eye witnesses say the IDF crushed her on purpose; Israel disputes the claim.

*** For example, if you track the stock dividends of just the perennial top five “defense contractors” based on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) you find dizzying increases in the decade that followed September 11, 2011: Lockheed Martin (LMT) equals 680 percent increase in per-share stock dividends or 161 percent increase in Earnings Per Share (EPS); Boeing (BA) +250 percent or +635 percent EPS; Northrop Grumman (NOC) +250 percent or +187 percent EPS; General Dynamics (GD) +336 percent or +191 percent EPS; Raytheon (RTN) +190 percent or +400 percent EPS. Source: The Gospel of Rutba: War, Peace, and the Good Samaritan Story in Iraq.