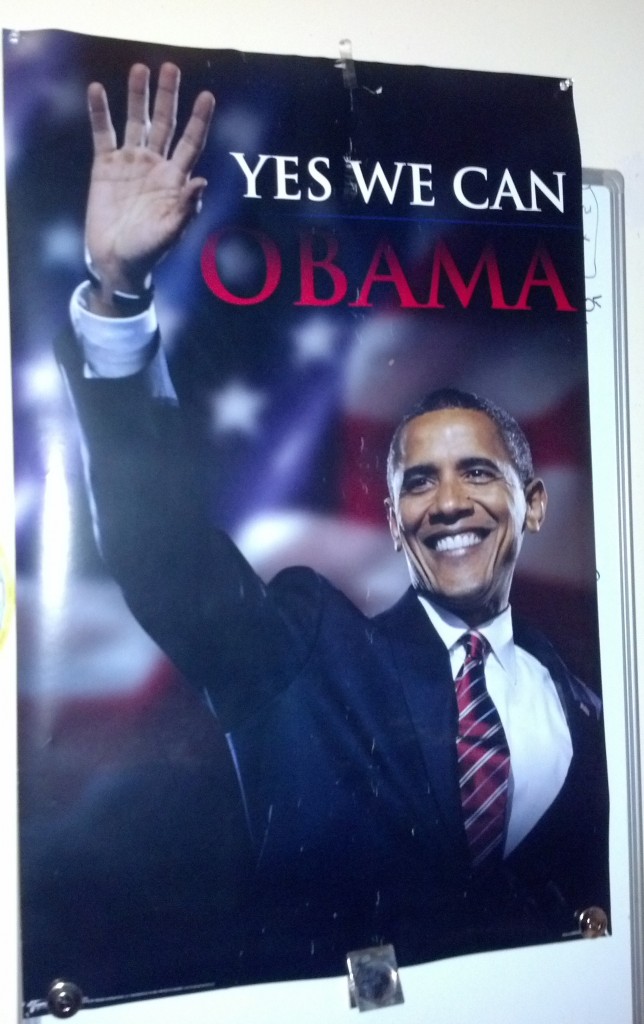

This day four years ago I had a large poster of presidential hopeful Barack Obama tacked to my office wall. He’s wearing a dark suit, white shirt, and the candidates’ perfunctory power tie; this one is burgundy with silver pinstripes. His gleaming white smile looks airbrushed and his right hand is raised in salute to a tide of supporters. So powerful, so commanding, it seemed that with a simple wave he could quiet Washington’s roiling and partisan Red Sea.

“Yes We Can,” the poster reads.

Eleven weeks after the election he presided over an adoring audience of some 1.5 million people crowded onto Washington’s Mall for inauguration day. Freezing temperatures and icy gusts didn’t stand a chance in the face of his radiance. To a nation and a world desperate for change it was like Obama could have fed those masses with two fish and five loaves.

To me, a print journalist wooed by his magnetism the morning after his 2004 convention speech (see “Democrats’ brightest shine at national convention“) the United States had elected a world leader. Finally. Given his multinational upbringing, Obama would surely tamp down mindless rhetoric about “American exceptionalism” and advocate instead for a united world. The White House and Washington would no longer be owned by K Street, Wall Street and Israel.

So I too drank of the Obama Kool-Aid. Tasted like miracle wine. I didn’t give a rat’s ass about his middle name (Hussein), birthplace (Honolulu or Jakarta made no difference to me) or, even, his religious pledge. Give me an earnest and honest Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu or Atheist over a misled, hypocritical Christian any day. Just, dear Lord, give me a wise and righteous leader.

Five months later, when President Barack Hussein Obama flew to Cairo and addressed the world’s 1.5 million Muslims, he quoted from the Talmud, the Quran and the New Testament. Amen Brother. Woot-woot!

By now I was thanking the heavens for Obama’s mama. Literally. I bowed my head and gave thanks for Stanley Ann Dunham. When Barack had been a schoolboy in Indonesia, the world’s largest Islamic nation, Stanley Ann had sent him to a neighborhood Catholic school and then to a predominantly Muslim school. At one he studied the catechism; at the other he learned about the muezzin’s call. On Easter or Christmas she might drag him to church, but she also took him to Buddhist temples, Chinese New Year celebrations, Shinto shrines, and to ancient Hawaiian burial sites. In The Audacity of Hope, Obama recalled how his mother, a stubborn secularist, believed that a good education required a working knowledge of all the world’s great teachings and religions.

So his inclusive speech in Cairo shouldn’t have surprised me. But after eight years of a professed born-again Christian residing over American politics, it did. I’d forgotten that U.S. presidents could be great.

“I come here to Cairo to seek a new beginning between the United States and Muslims around the world; one based upon mutual interest and mutual respect,” Obama said to a rapt audience at Cairo University on June 4, 2009. “There must be a sustained effort to listen to each other; to learn from each other; to respect one another; and to seek common ground. As the Holy Quran tells us, ‘Be conscious of God and speak always the truth.'”

From where her ashes had been spread along Oahu’s glorious Lanai Lookout, the late Stanley Ann (deceased for 17 years tomorrow) was living large in her son’s enlightenment. I was sure of it.

The election, inauguration, Cairo. Those were heady days. I was Obama intoxicated.

“Yes We Can.”

Of course we could. Why the hell had we waited so long?

Then, two years ago, I took Obama’s poster down. Rolled it up and put it away. No singular event inspired the action. No fit of anger or irrational spontaneity preceded it. However, I had thought it odd that a Nobel Peace Prize winner was championing the unmanned drones that routinely killed innocents alongside the (alleged) guilty. No judge or jury for either. Also, I’d noticed how the National Debt Clock near Times Square continued ticking off inconceivable amounts of gross debt. And in the wake of his inauguration, Congress had remained as partisan as ever, even more so.

Apparently Obama’s raised hand had quieted nothing. Perhaps no mere mortal could shed the weight of two wars, an economic collapse and Capitol Hill’s frat-house loyalties. Obama was human after all. Go figure. Maybe he was just another silk-tongued politician who had convinced us that he could work miracles. I suspect he’d even convinced himself.

So the poster came down. I was tired of looking at it and being reminded of the broken promise. Not the embellished campaign pledges that all candidates make; rather, the singular hope that had been fully inspired by our new multinational president. Obama inflated us and then let the air scream out. Nothing much changed under his watch. Looking at the poster every day only reminded me of that sorry fact. Of how the miracle wine had turned sour. Of how the hope that had risen in our throats as soon as McCain conceded began to taste like bile. Of how the post-election, post-Palin celebrations that flowed from Washington to London to Amman, Gaza, Baghdad and Tehran eventually went flat.

In Cairo, Obama had injected a decided sense of promise into global politics, Western, Far Eastern and Middle Eastern alike– Christians, Muslims, Jews, Hindus, Buddhists, all of us.

“It is easier to start wars than to end them. It is easier to blame others than to look inward. It is easier to see what is different about someone than to find the things we share,” he’d said, finishing his speech to a standing ovation. “There is one rule that lies at the heart of every religion– that we do unto others as we would have them do unto us. This truth transcends nations and peoples; a belief that isn’t new; that isn’t black or white or brown; that isn’t Christian, or Muslim or Jew.”

Then he’d corrected the behavior of our world’s three most warring faiths. Used their own words. Seared the lesson on them as if he were branding his mark on the world.

“The Holy Quran tells us, ‘O mankind! We have created you male and a female; and we have made you into nations and tribes so that you may know one another.’ The Talmud tells us: ‘The whole of the Torah is for the purpose of promoting peace.’ The Holy Bible tells us, ‘Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God.'”

Recalling that, I dug out the poster from the closet this week. It’s ripped and wrinkled and doesn’t hold much promise. On Tuesday I’ll vote again for Obama. (What are my choices, really?) But this time there will be no Kool-Aid, no dreaming, no inflated sense of change.

The only hope I hold is that the second time is the charm– not only the charmer.