“… for those spirit/truth seeking friends who long ago stopped trusting anything from a pulpit.”

~ Father Joe’s daily journals

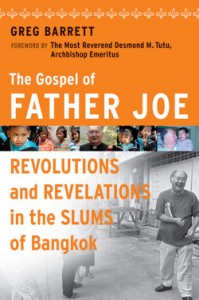

The Gospel of Father Joe: Revolutions & Revelations in the Slums of Bangkok

The Gospel of Father Joe: Revolutions & Revelations in the Slums of Bangkok

Winner of the Nautilus Book Award

- Read reviews

- Excerpts and Photos

- Purchase the book

See the book’s website at www.thegospeloffatherjoe.com

The Nautilus Book Award

The Gospel of Father Joe won the 2009 Nautilus Book Award Silver Medal in the category of “Conscious Media / Journalism / Investigative Reporting.” The Nautilus Book Awards honor and celebrate print and audio books of exceptional merit that make a literary and heartfelt contribution to spiritual growth, conscious living, high-level wellness, green values, responsible leadership and positive social change, as to the worlds of art, creativity and inspiration. The Silver Award winners are carefully selected in a three-tier judging process by an experienced team of book reviewers, librarians, authors, editors, bookstore owners, and leaders in the publishing industry.

Winning authors reflect the Nautilus Awards mission and include such distinguished authors and teachers as Deepak Chopra, Thich Nhat Hanh, Barbara Kingsolver, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Joel Osteen, Caroline Myss, and Marianne Williamson. Founder, Marilyn McGuire, has created the “Nautilus Library of Imagination & Possibility where all Nautilus Award winners are featured.

Winning authors reflect the Nautilus Awards mission and include such distinguished authors and teachers as Deepak Chopra, Thich Nhat Hanh, Barbara Kingsolver, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Joel Osteen, Caroline Myss, and Marianne Williamson. Founder, Marilyn McGuire, has created the “Nautilus Library of Imagination & Possibility where all Nautilus Award winners are featured.

Chapter 1: The Crucible

The story begins like the parable it’s become, in a no-man’s land with the seed of dreams strewn in the most foolish of places: slum rubbish. This was the 1970s when few people believed anything good could grow from the backwater of the undeveloped world. There were no official addresses or property deeds in the cordoned-off corners of Bangkok, nothing much for the municipal books, just putrid ground so primal and bleak that land was free for the staking. It’s where squatters pretended to own real houses and children made do with make-believe.

But these seeds were sown by an angry young Catholic chased from finer society. A priest, stubborn and cursing. The local Buddhists, Muslims, and Christians nurtured that seed, and in time the people and the priest, the abbot and the imam, worked together, as though the Buddha, Muhammad, and Jesus Christ were brothers and best friends. No doctrine, dogma, or creed was lorded. No growth tethered chapter to verse. The only belief that mattered was the one they shared. In the children. That was common, sacred ground.

Nourished like this, the seeds exploded with growth. There was a harvest, then another and another. The seeds grow still today, more than three decades later, a genus of hope thriving in the muck, as if it had been indigenous to the slums all along.

Tales of it grow too, spreading from those roots in Thailand to the media of North America and Europe, and in the retelling, it can begin to sound legendary. How in Gideon’s name does something grow from nothing and multiply like New Testament fishes and loaves? But nothing about it is myth. Every tale is true.

You can see for yourself when a new crop is gathered each year just before the yearly monsoons. For two, three, and often four days, a cordoned-off corner of the world blossoms in a brilliant hue of graduation gowns.

So it was on the sunstruck first week of March 2007—thirtythree years after the first seeds were planted.

The Mercy Centre preschool graduation was standing-room-only; moms, dads, aunties, uncles, siblings, cousins, the neighbor next door and next door to that one. Seven commencements stretched half the week and through a half dozen slums in celebration of seven hundred graduates from thirty-two schools built “officially illegally,” as the priest says, on the Thai government’s squatter land. Children six and seven years old accustomed to flip-flops and handme-downs strutted around in black mortarboard caps and matching silk gowns trimmed in a shade of blue my folk back home call Carolina. And while girls and their mothers and aunts fussed with lipstick and rouge, the boys did what boys do: swirl their heads until the tassels on their caps whir like the blades of a helicopter. Dizzy, they fall to the ground.

The priest was there, of course, more bald with each and every harvest. He conferred the diplomas and delivered the commencement address wearing the black and burgundy of Thailand’s revered Thammasat University. Draped across his left shoulder was a velvet sash with white stripes of cotton, thick enough to brush

and braid: three stripes in front, three in front, three in back representing the honorary rank of a Thammasat Ph.D. If you were new to the slums or to their graduation rituals, a sash like that in a place like that might stop you. It might even if you weren’t. Arriving at each school, the American known by tens of thousands of Thai as simply Khun Phaw Joe (“Mister Father Joe”) would park down a ways and out of sight. He’d pull on the gown, fix the sash just so, and then begin “the Walk”—a purposeful stride intended to put education on parade. Each route was different but familiar: past walls of plywood, lopsided floors, rusty tin roofs, and bare-bottomed babies; through humidity flavored by garbage and a subsistence watched over by sun-wrinkled village matriarchs who smiled even as they spit pinpoint tobacco-brown streams of betel nut juice. Heads turned to watch. Motorbikes slowed in deference. Cars stopped to let him pass. Old and young joined in, falling in behind or alongside, knowing full well where he was headed, knowing it was time.

In a backwater where nothing good was supposed to grow, graduation today is a rite of passage.

Some of the hardiest seed will scatter and continue maturing. There are graduates thriving now in the high school and college classrooms of North America with majors in economics, business, biology, computer science, and neuroscience. It’s why Khun Phaw Joe gave the Class of ’07 the same speech he has given every class since the Class of ’95, the same he will give the Class of ’08. Something about it seems to work.

As the Walk approached the first podium, the room fell silent. Pigeons gurgled their Rs, a mobile phone tweeted, somewhere a baby shrieked. Khun Phaw Joe waited. A small, heavy statue of the Virgin Mary sat in a May altar (on cloth surrounded by flowers) next to a Buddhist shrine of joss sticks and a portrait of the Thai monarch, Massachusetts native King Bhumibol Adulyadej, framed in gold leaf.

Fitted for kid-sized attention spans but fired like buckshot, the commencement address was aimed at everyone crowded into the ceremony.

Khun Phaw cleared his throat.

“If you don’t have anything to eat in the morning,” he began, speaking Thai and scanning his attentive audience of children, “then go to school!”

Most of the students sat erect or leaned slightly forward on the edge of their benches or chairs.

“If you don’t have any shoes to wear. . .,” he continued, pausing for effect, “go to school!”

“If Mommy or Daddy says you can stay home . . . go to school!

“If your friends want you to sell drugs . . . go to school!

“If Mommy gambles and Daddy’s a drunk . . . go to school!

“If all the money is gone and you can’t buy lunch . . . go to school!

“If your house burns down and you don’t have anything or anywhere to sleep . . . go to school!

“Go to school! Go to school! Go to school!”

Children joined in, louder and louder, chanting what sounded to me like “Tong by wrong rain high die!”

Go to school! Dhong bai rong rien hai dai! Dhong bai rong rien hai dai! Dhong bai rong rien hai dai!

Moms, dads, aunts, uncles, cousins, brothers, sisters, the neighbor next door joined in. Khun Phaw Joe directed the burgeoning chorus, his Thammasat gown waving until the bell sleeves billowed.

Dhong bai rong rien hai dai! Dhong bai rong rien hai dai! Dhong bai rong rien hai dai!

♦♦

And that’s the sprint from beginning to now, three decades of harvests. But in the journey, as in the parable, lie the lessons and wisdom of a social revolutionary who bucks convention, the law, and what the rest of us might consider common sense or self preservation.

The Reverend Joseph H. Maier, the eldest child of a philandering Lutheran father and pious Catholic mother, survived his own poverty and dysfunction to become a throwback of sorts: the durable, American-made export. It should be no surprise, then, that he settled on the wrong side of our economic divide and discovered

a comfortable fit. The neglected children of Klong Toey (three hard syllables sounding like a curse) would put a nice sheen of perspective on his own welfare beginnings.

Today, whenever Khun Phaw Joe feels a pang of self-pity, and often when he sees it rising in others, he quashes it with self-mockery and echoes of an earlier time: “Yeah, yeah, everybody hates me, nobody loves me, all I’m ever fed is worms. That’s my life story. Blah, blah, blah. . . . Well, guess what? The sun is rising, the rooster is calling, and another day is here. I guess ol’ Joe better get his ass out of bed and get going.”