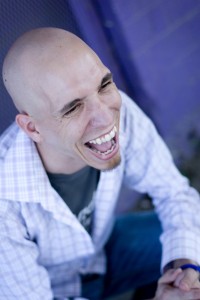

Jeremy Courtney, Author of “Preemptive Love: Pursuing Peace One Heart at a Time” and co-founder of the Iraq-based charity, the Preemptive Love Coalition. (Photo by Abigail Criner.)

When a native Texan named Jeremy Courtney took the stage at the 2012 Q Conference he had no idea he would, in effect, be pitching his 2013 memoir, “Preemptive Love: Pursuing Peace One Heart at a Time.”

Q conferences are progressive yet evangelical (yes, both) Christian forums, similar in format to the more secular TED talks. This particular Q (stands for Question) occurred in April 2012 in Washington, D.C., seven months before President Obama was reelected. More than 30 speakers ranging from a peacemaking Palestinian Christian (yes, both) to a hawkish Southern Baptist firebrand descended on Washington to inform, influence and otherwise inspire the nation’s sagging Christian majority (not to be confused with Moral Majority). In talks scaled to fit the capital’s rushed schedule and attention span, each speaker was allotted slots of three, nine or 18 minutes.

Courtney, a slender, shaved-headed humanitarian who looks more like a Buddhist than his native Baptist, had scored one of the conference’s grande sizes. Nine minutes. He’d fly six thousand miles from his home in Iraq to speak for less time than it took to board any of his connections. In the Andrew Mellon Auditorium, three blocks south of the White House, he paced on the stage in front of 700 Q “participants,” as the conference refers to its influential attendees. Nine minutes gave Courtney no time for colorful narratives, long anecdotes or drawn-out punchlines. He hardly had time to clear his throat. He got straight to the point.

“It wasn’t an easy morning,” he began, “when I woke up in Iraq with my wife and kids and found out that a fatwa had been issued against us calling for our death(s).”

You could have heard a phone vibrate inside the palatial seven-story auditorium. If he didn’t have them at fatwa (an official ruling given by Islamic clerics) he had them at death.

It was an evocative beginning to an amazing story (and now book) about a modern-day Gospel. Courtney’s memoir is the Good News of how mending the bodies of children restores hearts— literally and figuratively; theirs, ours and across “enemy” lines. In a blurb I wrote months ago for “Preemptive Love” (Howard Books, Oct. 1, 2013) I describe how the work of Courtney and his upstart international charity could “rewrite the hard wiring that holds humanity hostage.”

The hard wiring, in this case, is the fear that fractures humanity and keeps us locked in our comfort zones. It poses as pride, prejudice, and, often, as absolute faith. It can pit nation against nation, religion against religion, and, ultimately, it’s what drove an Iraqi mullah to order the death of Americans who were saving the lives of Iraqi children.

“Preemptive, what I mean by that is this act when we jump to help someone else, to serve another before they’ve done anything for us,” Courtney told to the Q audience. Early in his book he explains it this way:

“I had not named it yet— that passion and joy that caused me to suspend my questions and fears. My military friends had mantras like ‘Better to be judged by twelve than carried by six’ and ‘Shoot first; ask questions later.’ But I had watched Iraq destroy nearly all the people who allowed themselves to live in a constant state of suspicion or cynicism. So I adopted my own motto: ‘Love first; ask questions later.’ Today I call it preemptive love.”

Without any medical training and very little prep, he helped start an Iraq-based international development organization, Preemptive Love Coalition, which facilitates the heart surgeries needed for a massive backlog of sick Iraqi children. Iraqis have suffered three decades of war (beginning in 1980 with Iran), Saddam’s chemical weapons, 13 years of economic sanctions (1990-2003), and countless tons of the depleted uranium and white phosphorus used in U.S. munitions. Its healthcare system is decimated, and, contrary to the controversial findings in a recent World Health Organization study, doctors from across Iraq report alarming increases in cancer rates and congenital birth defects.

Not long after moving to Iraq in 2006 to help rebuild it, Courtney, who’d earned a masters degree in international studies from Baylor University, heard about tens of thousands of Iraqi children suffering from heart defects. On average there are 30 new cases every day in Iraq, he said at the sixth annual Q Conference. But to get the children to surgery, he and his Preemptive Love cohorts took a road less (read: dared not) traveled. At the time, they had no other choice.

Not long after moving to Iraq in 2006 to help rebuild it, Courtney, who’d earned a masters degree in international studies from Baylor University, heard about tens of thousands of Iraqi children suffering from heart defects. On average there are 30 new cases every day in Iraq, he said at the sixth annual Q Conference. But to get the children to surgery, he and his Preemptive Love cohorts took a road less (read: dared not) traveled. At the time, they had no other choice.

They sent Iraqi children to doctors in Israel. In other words, American Christians sent Iraq’s Muslim children to the Jewish state. To be saved. Literally.

In the fatwa, an Iraqi religious leader, or mullah, had used a phrase that immediately resonated with Courtney. “We must stop this treatment lest it lead our children to learn to love their enemies,” he recalled loudly at the Q Conference.

He paused, allowed the revelation to sink in.

“I was scared,’ he continued. “But I was thrilled by the mullah’s conclusion. We were saying the same thing: Be careful, preemptive love works.”

This threat from a high-ranking mullah was definitive evidence for him. It proved the efficacy of preemptive love. Hate could be recast by persistent, selfless acts of charity. War’s barbaric diplomacy could be repaired. Maybe, some day, an enlightened generation of Arab children would bridge the Middle East’s vast divide and make the region whole. Maybe the entire world could evolve.

“Every day in Iraq there seems to be an occasion to wake up again and make the decision to love indiscriminately,” Courtney said, describing for Q participants how his office had almost been blown up, his home broken into and bugged, his staff arrested on trumped-up charges. “Through these postures of preemptive love we’ve been able to go on and earn the trust of Muslims leaders across the country. We’ve made friends out of enemies.”

Eventually, a Muslim friend and sheikh in Iraq intervened on Courtney’s behalf and Preemptive Love continues its work in Iraq today. Better, it no longer needs to choose the road less traveled. Today it is helping to rebuild Iraq’s healthcare system by bringing surgeons into the country and training local doctors to perform the heart surgeries.

“I don’t have time to tell you all of the amazing things God is doing in the lives (of people) across Iraq,” he said, concluding his nine-minute talk, “but I’ll just tell you this: Violence unmakes the world but preemptive love unmakes violence. Preemptive love remakes the world.”

As he exited the Q stage and spoke with participants, a woman asked if she could buy a copy of his book in the store there in the Mellon Auditorium.

“I’ve not written a book,” he said. “I don’t have one in the store.”

She smiled confidently. “Would you like to have one in it?”

Turns out she was an acquisitions editor for a publishing house. That conversation led to others, which soon led to a top-tier literary agent (Chris Ferebee) and, several months later, Courtney signed a book deal with Simon & Schuster imprint, Howard Books. He was given five months to write the manuscript’s first draft.

Between frequent trips to his home near Lubbock, Texas and Preemptive Love’s work in Iraq, Courtney, now 34, expounded on his theology of preemptive love. His nine-minute Q talk quickly blossomed into an inspiring 230-page memoir. At its conclusion, near the end of the Afterword, he writes:

“Where you are sitting in the world as you finish this story may influence how you interpret my idea of preemptive love. If you are in the States, you may think first in terms of American kindness toward enemy Iraqis. If you are in Iraq, however, you may be more quick to see the countless times in this story in which the Iraqis acted first, offering protection, intervening, or taking a risk to welcome us in, even though we were often cast as their enemies. The truth is, preemptive love does not begin in the heart of humanity. Neither Americans nor Iraqis are inherently better at loving first than the other. We are all tribal, programmed to protect our own.

Instead, preemptive love originates in the heart of God. The one who made the universe and holds everything in it— the one to whom Muslims, Christians, and Jews are all ostensibly pointing— is the first and the last enemy lover.”

See video: JEREMY COURTNEY at 2012 Q CONFERENCE