[This posted earlier on The Huffington Post HERE.]

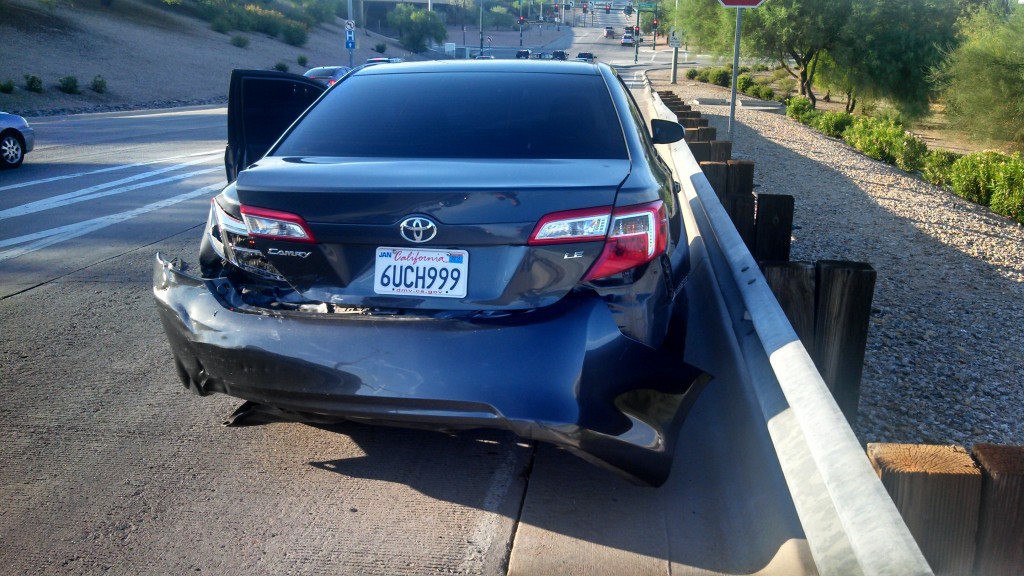

I felt it before I saw it, sort of like when a basketball leaves your fingertips with perfect trajectory. But this felt bad, not good. Last week a gray Dodge Charger barreled toward my rented Toyota Camry at reckless speed. I was idle at a stop sign. From my rearview mirror I could see the driver, his eyes bugging, mouth agape. His expression didn’t tell me anything I didn’t already know. I would be in a wreck. No way to avoid it. My evening was about to get complicated.

A dozen years earlier, a few months after 9/11 and in a crowded Cairo cafe, Egyptian playwright Ali Salem had leaned toward me through a haze of his own cigarette smoke. We were discussing the terrorist charges and countercharges being lobbed recklessly West to Middle East and vice versa — all the finger-pointing of politicians, preachers, imams and mullahs — when Salem told me something that applied to everyday life, something I’ve never forgotten:

“Words. Words are things.”

Salem, 66-years-old then, spoke with a deep baritone, and, much like actor James Earl Jones, the inflection of his rich voice conveyed as much as the English he spoke fluently.

“Good things begin with wooords. Bad things begin with wooords. So when we speak, we need to choose our words carefully.”

Going back even further, maybe five years before I’d interviewed Salem, I’d met someone else who had, in so many words, conveyed the same message. I’d just rear-ended her on Honolulu’s Ala Moana Boulevard. It was only a fender bender, but Hawaii uses an auto insurance law known as “no-fault.” What that means is that someone can rear-end you on Ala Moana and, in most cases, it’s considered to be no one’s fault. Legally speaking. The insurance company of the woman I’d rear-ended would assess the damage to her car and foot the bill. Mine would do the same for me. No fault. I know, right? Sounds crazy.

As I was apologizing profusely, she shushed me. Literally. Waved a finger in the air and told me, Shhhh.

“That’s why they’re called accidents,” she said, smiling maternally. “It’s okay. I’m okay. It was an accident.”

So, back to the Dodge Charger.

I’d flown into Phoenix’s Sky Harbor International Airport about 30 minutes earlier and rented my car from the same terminal where the Avis-rented Dodge originated. The driver of it, a water resources expert named Clay Landry, and I must have left at about the same time, both heading toward the Arizona 202 Loop via I-10 West. Roughly two miles from the airport there’s an awkward off-ramp to on-ramp combo that descends quickly toward an intersection. Too quickly if you’re pushing the 45-mph speed limit, and probably even if you’re not. Just before the stoplight a stop sign attempts to police four lanes of merging traffic. This is where I met Clay.

Funny thing about car accidents. Time is distorted. In the split second or less that I saw Clay’s crazed expression in my rearview mirror to when his Dodge plowed into the Toyota’s backside, I recall thinking: “Wow. No way to avoid this. It could be bad. Damn! I’m so hungry. I won’t be able to get dinner for another couple of hours.”

I probably looked angry as I climbed from the wreck. I wasn’t. I was hungry. It had already been a long day.

“Are you okay?” Clay shouted.

“I’m fine.”

“Are you sure?” he asked. “I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.”

I don’t recall thinking specially of the lady on Ala Moana Boulevard or of Ali Salem. Their seeds of humanity (owned by no religion and all religions) were planted more than a decade ago. However, I immediately felt compassion for Clay, who was uninjured but appeared to be rattled. I chose my words carefully and tried to reassure him.

“I’m fine. Really.”

I extended my hand.

“I’m Greg.”

“Clay.”

“It’s no problem, Clay. It’s okay. It’s why they’re called accidents.”